Common Lisp has a rich set of numerical types, including integer, rational, floating point, and complex.

Some sources:

Numbersin Common Lisp the Language, 2nd EditionNumbers, Characters and Stringsin Practical Common Lisp

Introduction

Integer types

Common Lisp provides a true integer type, called bignum, limited only by the total

memory available (not the machine word size). For example this would

overflow a 64 bit integer by some way:

* (expt 2 200)

1606938044258990275541962092341162602522202993782792835301376

For efficiency, integers can be limited to a fixed number of bits,

called a fixnum type. The range of integers which can be represented

is given by:

* most-positive-fixnum

4611686018427387903

* most-negative-fixnum

-4611686018427387904

Functions which operate on or evaluate to integers include:

isqrt, which returns the greatest integer less than or equal to the exact positive square root of natural.

* (isqrt 10)

3

* (isqrt 4)

2

Like other low-level programming languages, Common Lisp provides literal representation for hexadecimals and other radixes up to 36. For example:

* #xFF

255

* #2r1010

10

* #4r33

15

* #8r11

9

* #16rFF

255

* #36rz

35

Rational types

Rational numbers of type ratio consist of two bignums, the

numerator and denominator. Both can therefore be arbitrarily large:

* (/ (1+ (expt 2 100)) (expt 2 100))

1267650600228229401496703205377/1267650600228229401496703205376

It is a subtype of the rational class, along with

integer.

Floating point types

See Common Lisp the Language, 2nd Edition, section 2.1.3.

Floating point types attempt to represent the continuous real numbers using a finite number of bits. This means that many real numbers cannot be represented, but are approximated. This can lead to some nasty surprises, particularly when converting between base-10 and the base-2 internal representation. If you are working with floating point numbers, then reading What Every Computer Scientist Should Know About Floating-Point Arithmetic is highly recommended.

The Common Lisp standard allows for several floating point types. In

order of increasing precision these are: short-float,

single-float, double-float, and long-float. Their precisions are

implementation dependent, and it is possible for an implementation to

have only one floating point precision for all types.

The constants short-float-epsilon, single-float-epsilon,

double-float-epsilon and long-float-epsilon give

a measure of the precision of the floating point types, and are

implementation dependent.

ECL specifically bases its long-float on C’s long double, and thus has

higher precision:

CL-USER> (lisp-implementation-type)

"ECL"

CL-USER> most-positive-single-float

3.4028235e38

CL-USER> most-positive-double-float

1.7976931348623157d308

CL-USER> most-positive-long-float

1.189731495357231765l4932

Floating point literals

When reading floating point numbers, the default type is set by the special

variable *read-default-float-format*. By default

this is SINGLE-FLOAT, so if you want to ensure that a number is read as double

precision then put a d0 suffix at the end

* (type-of 1.24)

SINGLE-FLOAT

* (type-of 1.24d0)

DOUBLE-FLOAT

Other suffixes are s (short), f (single float), d (double

float), l (long float) and e (default; usually single float).

The default type can be changed, but note that this may break packages

which assume single-float type.

* (setq *read-default-float-format* 'double-float)

* (type-of 1.24)

DOUBLE-FLOAT

Note that unlike in some languages, appending a single decimal point to the end of a number does not make it a float:

* (type-of 10.)

(INTEGER 0 4611686018427387903)

* (type-of 10.0)

SINGLE-FLOAT

Floating point errors

If the result of a floating point calculation is too large then a floating point overflow occurs. By default in SBCL (and other implementations) this results in an error condition:

* (exp 1000)

; Evaluation aborted on #<FLOATING-POINT-OVERFLOW {10041720B3}>.

The error can be handled, or this behaviour can be

changed, to return +infinity. In SBCL this is:

* (sb-int:set-floating-point-modes :traps '(:INVALID :DIVIDE-BY-ZERO))

* (exp 1000)

#.SB-EXT:SINGLE-FLOAT-POSITIVE-INFINITY

* (/ 1 (exp 1000))

0.0

The calculation now silently continues, without an error condition.

A similar functionality to disable floating overflow errors exists in CCL:

* (set-fpu-mode :overflow nil)

In SBCL the floating point modes can be inspected:

* (sb-int:get-floating-point-modes)

(:TRAPS (:OVERFLOW :INVALID :DIVIDE-BY-ZERO) :ROUNDING-MODE :NEAREST

:CURRENT-EXCEPTIONS NIL :ACCRUED-EXCEPTIONS NIL :FAST-MODE NIL)

Arbitrary precision

For arbitrary high precision calculations there is the computable-reals library on QuickLisp:

* (ql:quickload :computable-reals)

* (use-package :computable-reals)

* (sqrt-r 2)

+1.41421356237309504880...

* (sin-r (/r +pi-r+ 2))

+1.00000000000000000000...

The precision to print is set by *PRINT-PREC*, by default 20

* (setq *PRINT-PREC* 50)

* (sqrt-r 2)

+1.41421356237309504880168872420969807856967187537695...

Complex types

There are 5 types of complex number: The real and imaginary parts must be of the same type, and can be rational, or one of the floating point types (short, single, double or long).

Complex values can be created using the #C reader macro or the function

complex. The reader macro does not allow the use of expressions

as real and imaginary parts:

* #C(1 1)

#C(1 1)

* #C((+ 1 2) 5)

; Evaluation aborted on #<TYPE-ERROR expected-type: REAL datum: (+ 1 2)>.

* (complex (+ 1 2) 5)

#C(3 5)

If constructed with mixed types then the higher precision type will be used for both parts.

* (type-of #C(1 1))

(COMPLEX (INTEGER 1 1))

* (type-of #C(1.0 1))

(COMPLEX (SINGLE-FLOAT 1.0 1.0))

* (type-of #C(1.0 1d0))

(COMPLEX (DOUBLE-FLOAT 1.0d0 1.0d0))

The real and imaginary parts of a complex number can be extracted using

realpart and imagpart:

* (realpart #C(7 9))

7

* (imagpart #C(4.2 9.5))

9.5

Complex arithmetic

Common Lisp’s mathematical functions generally handle complex numbers, and return complex numbers when this is the true result. For example:

* (sqrt -1)

#C(0.0 1.0)

* (exp #C(0.0 0.5))

#C(0.87758255 0.47942555)

* (sin #C(1.0 1.0))

#C(1.2984576 0.63496387)

Reading numbers from strings

The parse-integer function reads an integer from a string.

The parse-number library cannot evaluate arbitrary expressions, so it should be safer to use on untrusted input. It can also parse floats.

* (ql:quickload :parse-number)

* (use-package :parse-number)

* (parse-number "23.4e2")

2340.0

6

The Serapeum library of course has a parse-float

function too. You can even ask it the output type, for example, a double float:

* (ql:quickload "serapeum")

* (serapeum:parse-float "23.4e2" :type 'double-float)

2340.0d0

;; ^^ double

See the strings section on converting between strings and numbers.

Converting numbers

Most numerical functions automatically convert types as needed.

The coerce function converts objects from one type to another,

including numeric types.

See Common Lisp the Language, 2nd Edition, section 12.6.

Convert float to rational

The rational and rationalize functions convert

a real numeric argument into a rational. rational assumes that floating

point arguments are exact; rationalize exploits the fact that floating point

numbers are only exact to their precision, so can often find a simpler

rational number.

Convert rational to integer

If the result of a calculation is a rational number where the numerator is a multiple of the denominator, then it is automatically converted to an integer:

* (type-of (* 1/2 4))

(INTEGER 0 4611686018427387903)

Rounding floating-point and rational numbers

The ceiling, floor, round and truncate functions

convert floating point or rational numbers to integers. The difference

between the result and the input is returned as the second value, so that the

input is the sum of the two outputs.

* (ceiling 1.42)

2

-0.58000004

* (floor 1.42)

1

0.41999996

* (round 1.42)

1

0.41999996

* (truncate 1.42)

1

0.41999996

There is a difference between floor and truncate for negative

numbers:

* (truncate -1.42)

-1

-0.41999996

* (floor -1.42)

-2

0.58000004

* (ceiling -1.42)

-1

-0.41999996

Similar functions fceiling, ffloor, fround and ftruncate

return the result as floating point, of the same type as their

argument:

* (ftruncate 1.3)

1.0

0.29999995

* (type-of (ftruncate 1.3))

SINGLE-FLOAT

* (type-of (ftruncate 1.3d0))

DOUBLE-FLOAT

Comparing numbers

See Common Lisp the Language, 2nd Edition, Section 12.3.

The = predicate returns T if all arguments are numerically equal.

Note that comparison of floating point numbers includes some margin

for error, due to the fact that they cannot represent all real

numbers and accumulate errors.

The constant single-float-epsilon is the smallest

number which will cause an = comparison to fail, if it is added to 1.0:

* (= (+ 1s0 5e-8) 1s0)

T

* (= (+ 1s0 6e-8) 1s0)

NIL

Note that this does not mean that a single-float is always precise

to within 6e-8:

* (= (+ 10s0 4e-7) 10s0)

T

* (= (+ 10s0 5e-7) 10s0)

NIL

Instead this means that single-float is precise to approximately

seven digits. If a sequence of calculations are performed, then error

can accumulate and a larger error margin may be needed. In this case

the absolute difference can be compared:

* (< (abs (- (+ 10s0 5e-7)

10s0))

1s-6)

T

When comparing numbers with = mixed types are allowed. To test both

numerical value and type use eql:

* (= 3 3.0)

T

* (eql 3 3.0)

NIL

Operating on a series of numbers

Many Common Lisp functions operate on sequences, which can be either lists or vectors (1D arrays). See the section on mapping.

Operations on multidimensional arrays are discussed in this section.

Libraries are available for defining and operating on lazy sequences, including “infinite” sequences of numbers. For example

- Clazy which is on QuickLisp.

- folio2 on QuickLisp. Includes an interface to the

- Series package for efficient sequences.

- lazy-seq.

Working with Roman numerals

The format function can convert numbers to roman numerals with the

~@r directive:

* (format nil "~@r" 42)

"XLII"

There is a gist by tormaroe for reading roman numerals.

Generating random numbers

The random function generates either integer or floating point

random numbers, depending on the type of its argument.

* (random 10)

7

* (type-of (random 10))

(INTEGER 0 4611686018427387903)

* (type-of (random 10.0))

SINGLE-FLOAT

* (type-of (random 10d0))

DOUBLE-FLOAT

In SBCL a Mersenne Twister pseudo-random number generator is used. See section 7.13 of the SBCL manual for details.

The random seed is stored in *random-state* whose internal

representation is implementation dependent. The function

make-random-state can be used to make new random

states, or copy existing states.

To use the same set of random numbers multiple times,

(make-random-state nil) makes a copy of the current *random-state*:

* (dotimes (i 3)

(let ((*random-state* (make-random-state nil)))

(format t "~a~%"

(loop for i from 0 below 10 collecting (random 10)))))

(8 3 9 2 1 8 0 0 4 1)

(8 3 9 2 1 8 0 0 4 1)

(8 3 9 2 1 8 0 0 4 1)

This generates 10 random numbers in a loop, but each time the sequence

is the same because the *random-state* special variable is dynamically

bound to a copy of its state before the let form.

Other resources:

- The random-state package is available on QuickLisp, and provides a number of portable random number generators.

Bit-wise Operation

Common Lisp also provides many functions to perform bit-wise arithmetic operations. Some commonly used ones are listed below, together with their C/C++ equivalence.

| Common Lisp | C/C++ | Description |

|---|---|---|

| (logand a b c) | a & b & c | Bit-wise AND of multiple operands |

| (logior a b c) | a | b | c | Bit-wise OR of multiple operands |

| (lognot a) | ~a | Bit-wise NOT of single operands |

| (logxor a b c) | a ^ b ^ c | Bit-wise exclusive or (XOR) of multiple operands |

| (ash a 3) | a << 3 | Bit-wise left shift |

| (ash a -3) | a >> 3 | Bit-wise right shift |

Negative numbers are treated as two’s-complements. If you have forgotten this, please refer to the Wiki page.

For example:

* (logior 1 2 4 8)

15

;; Explanation:

;; 0001

;; 0010

;; 0100

;; | 1000

;; -------

;; 1111

* (logand 2 -3 4)

0

;; Explanation:

;; 0010 (2)

;; 1101 (two's complement of -3)

;; & 0100 (4)

;; -------

;; 0000

* (logxor 1 3 7 15)

10

;; Explanation:

;; 0001

;; 0011

;; 0111

;; ^ 1111

;; -------

;; 1010

* (lognot -1)

0

;; Explanation:

;; 11 -> 00

* (lognot -3)

2

;; 101 -> 010

* (ash 3 2)

12

;; Explanation:

;; 11 -> 1100

* (ash -5 -2)

-2

;; Explanation

;; 11011 -> 110

Please see the CLHS page for a more detailed explanation or other bit-wise functions.

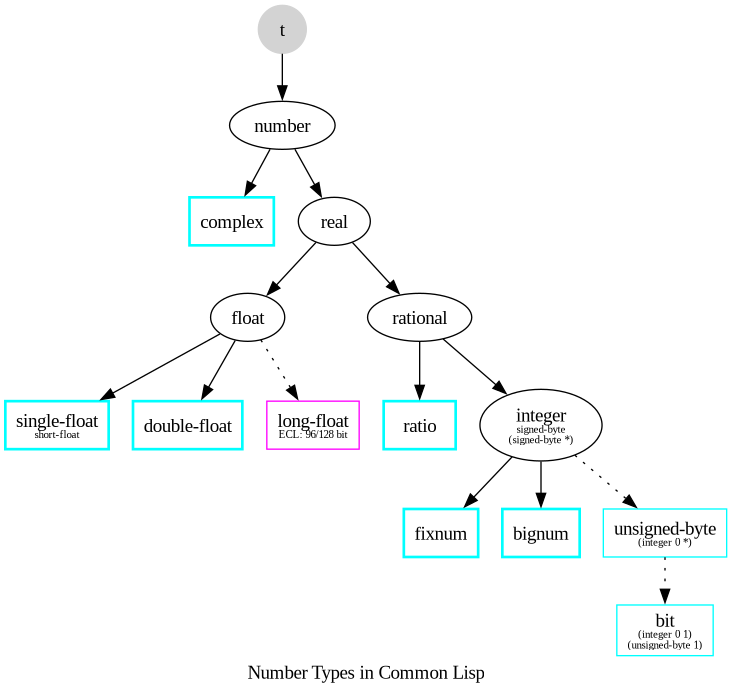

Appendix: the number tower

Types in bold, solid boxes are the ones you will typically use.

Page source: numbers.md